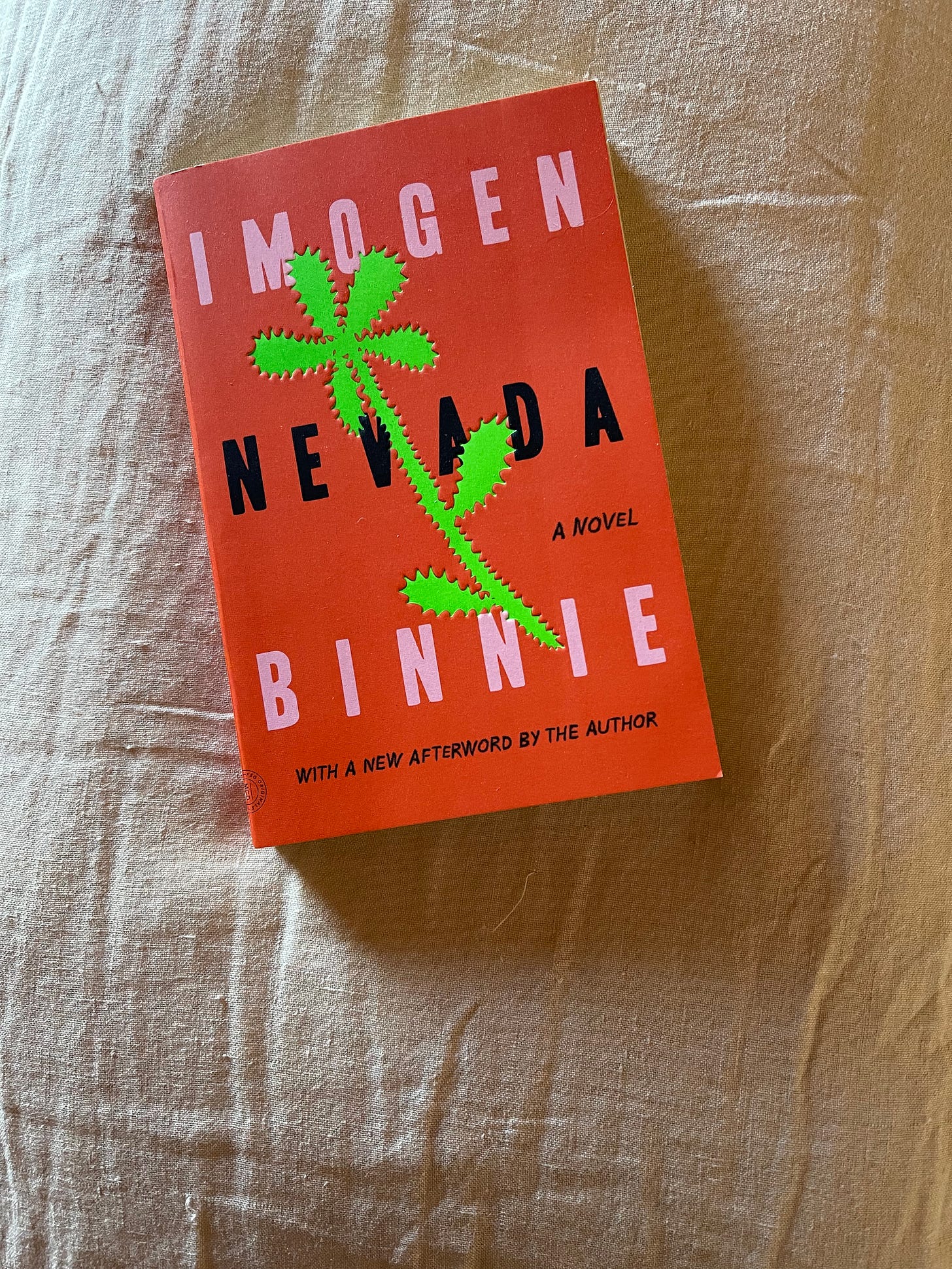

This fucking book. I don’t even have to tell you to read it because if you pick it up and get two sentences in, you will. It’s a riptide.

One criterion of books which we leave unspoken to a really fucked up degree, imo, is how much you actually want to … read them. As in, eat your sandwich with one hand so you can keep reading. Stay up all night. Take them with you into the bathroom. I’ve evolved a tremendous mistrust of book hype because I have picked up so many of the drooled-over must-reads of the last ten years and found them to be stodgy, overwritten, narcotically boring, horribly cynical. I don’t know how you guys manage to even turn the pages of some of these books. And honestly, maybe you don’t—maybe you just put pictures of them on Instagram and tell people that they were like, so good. OMg. So good. because you’re also baffled by their popularity. Which is fine (well, it isn’t, but it does certainly seem to be the way things are).

What I’m saying is, Nevada cuts through the bullshit, and you will just be read read reading it before you know what hit you. It has that sure-footed magnetism that some books have. And sure, no accounting for taste, probably lots of people truly enjoy (somehow?) those slabs of literary fiction where like, a woman is jogging and looking at things, or a poor beset creature is filled with slings and arrows. Probably the same people are deeply disinterested in a degree of self-conscious intelligence trained upon an ever-flat affect which refuses to present embodied emotion without at least some form of heroic distraction by means of beer or cathartic bike rides or the brief glory of coming in from the rain. Show don’t tell, etc. Nevada isn’t for those people. But it definitely is for me. (By which I mean I loved it, and it made me glad to be alive.)

And that might be a weird thing to say because I’m not trans, and I don’t really identify anywhere particularly liminal within the gender spectrum—I mean, I think bridal showers are nightmarish rehearsals of compulsory hetero strangeness, and I’ve never really shaved my legs or whatever, but I love black liquid eyeliner and red lipstick and rhinestone sunglasses, and I feel like girl shit has always suited my purposes for performance and self-definition just fine. Gender dysphoria is not a major plot line in my life.

But I have felt—for truly no reason I can explain to you—an adult who lived in a childhood that felt perpetually wrong, self-conscious, self-policing, alert for the ways in which something about me was troublesome to other people. There is an endless loneliness in me. There just is. I can’t manage to scrape together the kind of feelings other people have about what’s supposed to be sad or happy, but I have a lot of feelings about things so minor that they make me seem (/be, maybe) kind of crazy. And even though that degree of self-alienation was never connected to a feeling of not-girl-ness or whatever else, I relate big time to the interior of Maria.

My capacity to relate to this book is not its primary value, obviously. Nevada’s cult status has been well documented and lived by lots of people ages ago. It was a massive innovation for a book with a trans character to narrate lived experience directly, without expository asides about the mood stability consequences of going too long between hormone shots. Maria reflects on highly granular aspects and conflicts within the pre-social media trans experience which you would only otherwise get by reading the strap-on.org message board, and as such, I’ve seen it described as a kind of primer for those whose eggs have just cracked. And maybe, for that reason, readers like me have kept a distance from this book? But I think there can be a kind of unintentional bigotry to siloing novels and audiences based exclusively on their lived experience and ability to relate to the character’s primary identity markers. I would argue that the re-release of this book from a now defunct indie to FSG/MCD is an invitation of some kind to engage with the idea of a trans novel having a second life with a larger audience. So there are all of the brackets and attenuations that I feel are possibly necessary for me to express before I say that in Nevada I recognized myself to a degree that made me want to live a bigger life, made me want to fight the battle to be present, made me realize, oh shit, the mind will starve you. But the body has the answers.

Nevada’s plot follows Maria, a bookseller who spontaneously escapes her life in a cross-country trip (stealing her ex’s car, no less). Her relationship has imploded in part because her affect is so flat that it doesn’t permit any risk or intimacy. Which she gets—she gets everything. She is so smart and riffy and aware that it is deeply entertaining to follow her on a regular ass day of getting to work late and sneaking out for a bagel. She’s in an odd place because she has already crossed one massive internal threshold by coming out and living as a trans woman, but somewhat annoyingly, there is another threshold before her. Something is missing. Parts of her are absent.

On her trip, she finds James in Star City, Nevada, a stoner working at Walmart and hiding vistas of shame and ennui and excitement from his girlfriend. James is trans and doesn’t quite know it yet. Maria recognizes this psychic imprint by pure electrical intuition, and she tries to help him along with the process of discovering himself.

In a lesser version of this novel, she would succeed. And everyone would cry happy pride month branded tears of relief. But in a way, that would dehumanize all involved. Instead, the novel concludes in a surprising, angular way which leaves everyone in unresolved situations, and probably some of this comes down to personal taste/how much you need your book to tie your shoelaces into secure little bunny ears for you, but I think it’s a highly effective ending because what it seems to resolve is the fact of psychological complexity for these characters. There is no destination, no lesson, no sentimental little snow globe you get to keep at the end. But why do you need a tchotchke if, instead, you can feel alive?

Life is good, by the way. I’ve been in one of those monastic periods where the thought of sharing anything with the world feels like being thrown naked into ice-cold water. Don’t know why that happens; I suppose I would be a better self-marketing artist if I could push through those times and grind out some personal essays about the very same experience.

But I also think there’s value in staying outside the “discourse” for extended vacations, at least so I don’t end up sounding like everyone else. A lot of people wrote to me after my response to Roe being overturned because they found it refreshing that I didn’t say the same five things everyone else says. I’m glad about that. I hate how swiftly a cutesy little turn of phrase will infect the entire internet (“gorgeous, gorgeous girls,” “many such cases,” “bold of you to assume …”) until it is ironized, pulverized, or totally forgotten about. I dream of a future where social media is regulated for un-soul-destroying amounts of attention span ravage. We’re all going to look back at this as a super fucked and spooky time of reiterating thoughts that aren’t really ours.

But monastic life doesn’t satisfy forever. I’m constantly looking for a way to come down off the mountain (literally at this point, lol). I miss the way that I got to be close with people when I was playing in the Mayday Marching Band, or when I played in a friend’s small ensemble for a one-night performance of his Thaddeus Mosely tribute concerto. When you practice music with other people, you breathe at the same time. You communicate constantly. You delight each other. There’s a lot of body in it, figuring out how to navigate silence with other people. And time. Sometimes I think I could have a very satisfying other life as a session musician. Like the wrecking crew, to just show up and drop in and play the changes with a kind of soul and humility.

I bought my dream guitar last week. I met a very nice Christian dad (judging from the sheet music in the trunk of his minivan) in the parking lot of an Islands Fine Burgers and Drinks in Fullerton and gave him an envelope of cash for a blue Fender Jazzmaster. And I feel like I’m too old for this: too old to be writing songs for the first time, too old to learn an instrument, too old to want to. But I don’t believe in “too old” for other people, so why would I believe in it for me?