My book is finished! I am happy with it. Happier than I was with it before, even. And I learned a great secret while I was finishing it, which you may wish to know if you are also in the business of finishing a book. (Or anything really.)

Here it is:

Decide.

Maybe that’s not it for everybody, but for me, a notoriously flaneusy swampy reading 5 books at once kind of person, deciding is it. The one thing I was not previously willing to do. One great skill I have as a writer is that I can see a connection between two things. Any two things. If you give me two words, an image pops into the invisible space between them. It’s like watching a wonderful movie all the time. (Is it like this for everyone?)

And sort of similarly with stories: The only difference between a sad story and a happy one is where you drop the frame, because “good thing” and “bad thing” are produced by contexts developed by the setup of a story. If I look, I can find anything. (And this, more than any supposed moral gold nugget hunting, may be the real value of storytelling to humans: It is an exercise in meaning making and relativity through the construction of a point of view.)

But the problem with those skills is that they can lead you anywhere, even far away from the book you want to write. Unless, of course, you decide what that is and can use your connecting mind to get there.

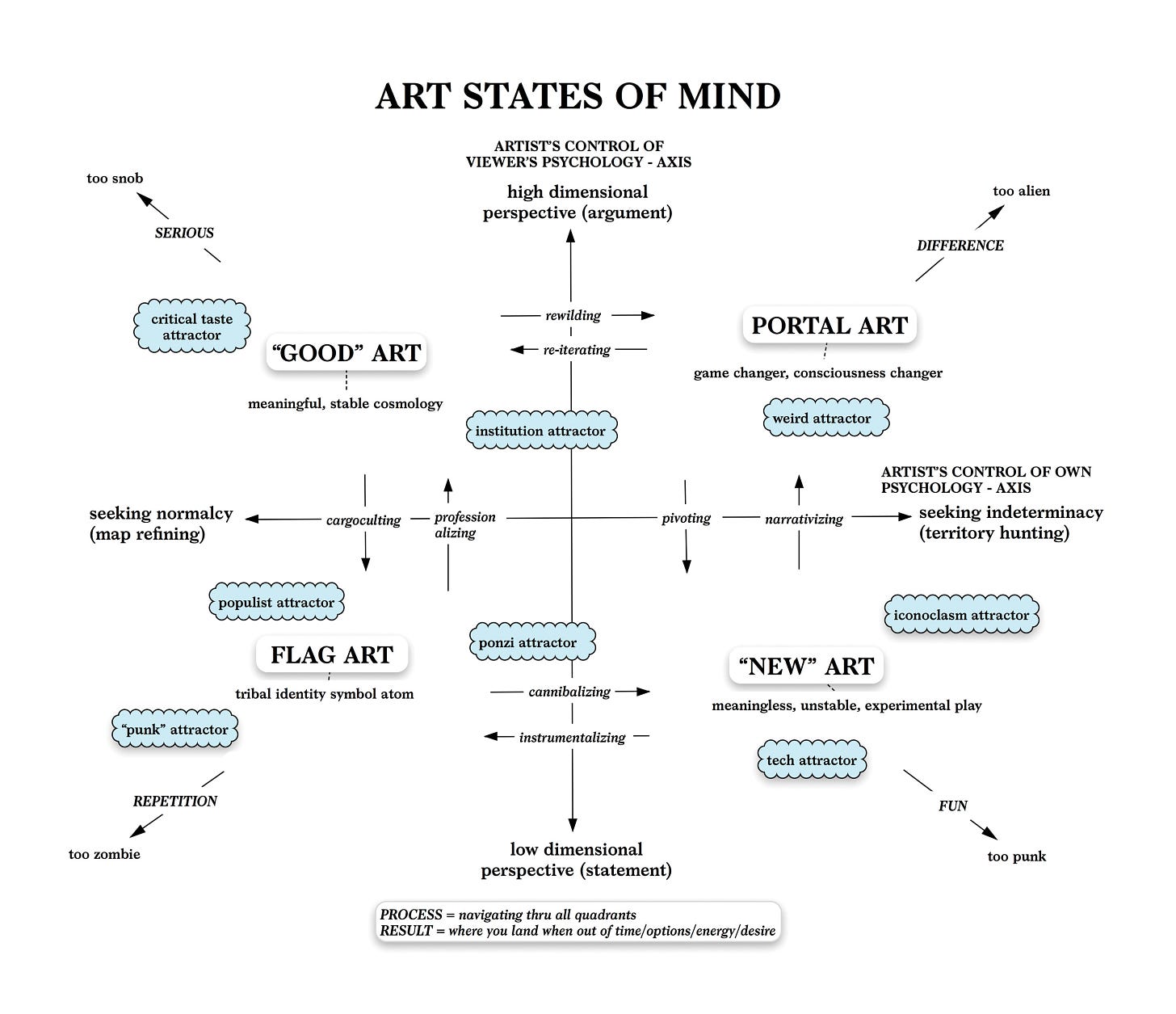

One day on Instagram (let us never again say Instagram hasn’t done us any favors), I came across this scatter plot chart by Ian Cheng:

As soon as I saw PORTAL ART I thought: Yes! That Is Me! That is IT. Weird attractor! seeking indeterminacy! And as soon as I saw “GOOD” ART I thought: oh my god, that’s what people in writing workshops are trying to get me to do. And maybe this is why some people find my work aloof or impossible to feel. Because if you’re looking for normalcy—“map refining”—you will be frustrated by portal art.

I had always known that writers working on multigenerational family sagas and writers working on art world love triangles taken over by a cosmic horror element (that’s me, babe) were in pursuit of radically different things. But I had never realized that “good” art might be considered a totally separate category, almost a genre, with its own set of ambitions. I mean, yes, that’s essentially what literary fiction means. But somehow, in many institutional literary spaces, there’s a lack of clarity about what exactly we’re all going after; it’s understood that, no matter what subject and materials you’re using, everyone is basically trying to make “good” art, making “good” art the invisible default, attributing all qualities of departure and difference outside of itself.

One of Charlie Baxter’s first rules of workshop: No owl criticism. And what did he mean by that? He meant to discourage you from saying something like: “This story is about owls … and I don’t like owls.” In other words, the writer’s choice of subject is not going to be part of the criticism, not even as a means of disengaging with it.

But I think that idea could be usefully extended to the writer’s choice of objective, too. Which would mean asking: Does the piece exhibit control over the reader’s psychology in a way that produces/allows for, in the case of flag art or “new” art, a clear statement? Does the piece exhibit control over the reader’s psychology in a way that produces/allows for, in the case of “good” art or portal art, a clear question?

Readers who are looking for a clear statement will find a clear question elusive and dissatisfying. Readers who are looking for a clear question will find a clear statement boring and dissatisfying. These different hypothetical readers can still be useful to each other if they have enough awareness to step outside of their default preferences, but in my experience, most people in workshops don’t read that way.

Workshops are supposed to be useful because they give you a testing ground for seeing how readers might talk about your story, but they totally and completely ignore the fact that not everyone is your reader. In fact, most people are not your reader. And if you want to break through to any readers at all, the quickest way is to swing for the fences in a way that would thrill your ideal reader, rather than wasting any time attempting to argue for the validity of your tastes or your interests.

If I were Cambridge Analytica and I was going to make a psychographic to find my aesthetic peers, friends, and readers, my first filter would probably be: Do you like Twin Peaks? (And then: Denis Johnson? Larry Levis? Mary Ruefle? Roberto Bolaño? Do you have a little bit of a pop song heart in spite of/in addition to the mystery and occasional aridity of the above? Will you mind if I insinuate, just slightly and mainly through the quality of consciousness evident in images, that everything is alive and the world is a dream observed by a dream? Does fiction bent toward social justice kind of bum you out, but you feel compelled to conceal this fact? Do you get why a little bit of crassness and ugliness is necessary to make all this work, like burnt edges on toast? Will you understand that by rendering a world in these ways, I am giving you the best of my heart and not trying to trick or deceive you?)

But my point being, I would start with Twin Peaks, because it is a broadly known thing which effectively guides you to the quadrant I wish to inhabit. And if you don’t want to visit that quadrant, it’s best if you go with someone else.

The trouble with finishing my second novel was simply this: I was afraid of deciding where to land with this book. As this endlessly brilliant chart notes, the creative process entails trying all of these states of mind before landing on one, and I had been putting off the decision. I could write a flag art version of it which produced a statement about how institutional art invokes beauty through power and sometimes cruelty. The main male character would be, in this version of the book, pretty much evil, but that had never felt quite right to me. I could write a “good” art version of the book invested in a stable cosmology (psychological realism, hayyyy). But that never felt right to me, either. And in fact, the whole book began with a screed about the failings of psychological realism (against the tyranny of being expected to make sense). Or I could write the portal art version of this book, which would really be about a leap in a character’s consciousness, following them through the portal.

As you might guess, the third one is the one that I’m most interested in. But I was afraid of committing to it because I just kept thinking about all the times in workshop some ex-sorority Ivy League norm told me that I didn’t make any sense. (How about this, you don’t make sense to me either, lady.) I kept thinking about all the times people have called me crazy, the Goodreads review that told me I should just kill myself because I’m so pretentious (even, schade, in a book where I was trying to be direct and unpretentious), the implication growing up that by just being myself I was trying to make other people feel bad about themselves.

It might seem brave to some people to talk candidly about, or tell stories about, idk, alcoholism, oppression, workplace sexual harassment, etc. But when I talk about my experience of those things, it feels pretty whatever-whatever. Somehow, that isn’t really where the risk is for me. I can talk about that stuff all day and still feel hidden because those things are really not central to how I see the world.

The events and topics that seem to arouse sympathy, pity, connection, emotion in other people—I just don’t get it. I have a lot of friends who want to connect over a shared sense that the world is doomed and everyone is fucked and everything is bad and honestly? I don’t want to connect that way. I don’t agree. I don’t think despair makes someone smart. I don’t think that anybody knows what’s going to happen next, and treating negativity bias like an oracle is just as distorted as seeing everything through toxic positivity. I try to hide this because it seems like this is how the world connects. I’m afraid people will think I’m callous or unkind or invalidating.

You might wonder what any of that has to do with telling stories—but stories are one of the most ubiquitous tools we use to develop a sense of how the world works. They present certain decisions about trauma and time as reality. And my basic feelings about the world are: it is beautiful. It is beautiful. Beauty is inhuman because it sometimes seems cold and terrifying. And empty. But it is beautiful. And maybe being human isn’t really the most important thing about us. Maybe good and bad and suffering are less fact and more like tone colors in an opera. It’s all realism, if you’re willing. Nothing is real. Magic is real.

Risk is the basic medium for all artists, narrative or not. For me, the real risk is in being as weird as I am. That’s what putting it all on the line looks like for me. And I think that’s the risk that will connect to the readers I want to make sense to.

The whole revision process became extremely simple once I realized that I had been reading the book through the eyes of a hypothetical person who was dubious and judgmental about my whole point of view. No wonder it felt kind of like, bad and confusing to work on! So I stopped doing that, and instead, I pretended that I was David Lynch reading my book. Everything became easy. Decisions that I didn’t know how to make were clear. I could read the book with appreciation instead, and let it breathe.

God knows not every creative project contains a dollhouse version of some deep, soul-level problem. (Or: I hope not!!!!!!!! Haha!!?) Maybe this is why the second book is such a tricky thing for some of us: your first book is just one data point. The second book adds another dimension. The second data point could go anywhere, lead anywhere. Readers can and will look at a book from any number of directions, but with two books it’s possible to draw a line connecting them. And some people who loved the first book will be like: eww, what? Go over there? Whatever ways you hid in the first book become the places where you have to unhide yourself in the second. I’m sure other writers have other reckonings—and I know this because risk is the medium. But I think my angsty ur-journey is over. I’m excited because I want to move into a new form of risk: the risk of more, bigger, let’s see how high it goes. Now that I’m willing to be seen, maybe I’ll be willing to sing, too.

I don’t think you can make art without forgiving the world, because it’s a gift. And there’s really no way to give a gift resentfully. But that’s exactly what I have been doing: trying to be the sweetie-pie I think you want, and hating you for it.

Telling the story of despair! Ugh! OK!

But I hope you can forgive me. You, who have always been so splendid and generous.

Very well said. A telling in itself! Put me in line for this novel!

Omg SARAH!!!!!!! YES YES YES!!!