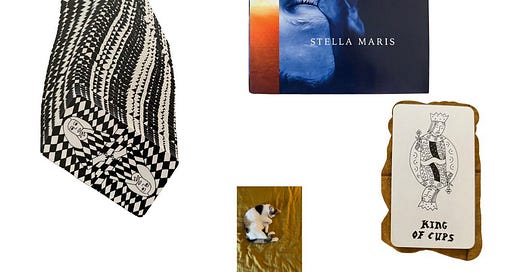

the king of cups, and a selection from Cormac McCarthy’s Stella Maris:

“When I was a child I used to daydream about living in some faraway place. I was always plotting how to get there.

An imaginary place or a real one?

I think you start with the imaginary. Later you get serious and you dig out the atlas.”

the aleatory

This week, I’m at the Altadena Public Library. I’m wearing new shoes—high-top checkered Vans.

I went to assume my favorite seat, the Eames chair by the new poetry books that looks out onto the ferns beyond the beautiful wall-high windows, but just before I got there, a man appeared out of nowhere and sat down.

He was also wearing high-top Vans.

We briefly noticed this about one another.

For a moment, it almost looked as if he were going to abandon the seat out of some deference (perhaps) to my intensity. But he sat down.

I retreated to another seat, one which still faces the ferns, but which is maybe 30% better because you can also see the mountains and the incense cedar across the street.

. . /

A few months ago, I went to see Alejandro Jodorowsky speak on the topic of psychomagic—an invented shamanic healing modality in which he heals psychological wounds through the creation of pageantry and ritual.

This might mean painting menstrual blood on a mirror and hanging it covertly in a museum, or taping a picture of your family to an enormous pumpkin and beating it to smithereens in a Parisian alleyway.

It was billed as a “psychomagic workshop,” which I found very intimidating. To me, “workshop” implies the idea of participatory action, and I imagined it might involve Jodorowsky healing psychological wounds in real time. Maybe he would somehow just know our psychological wounds by looking at us. This did not seem beyond possibility.

Of course, I knew that the event was being held at the Egyptian Theater, so it would not be intimate. I could be safe, if I chose. But I am often animated by a senseless cloud of staticky aliveness which makes me raise my hand and say things in such situations.

But there was no need to worry. It turned out that the main point of the day was to screen Psychomagic, a film documenting several healing performances and rituals.

Upon appearing on stage, Jodorowsky declared that he did not care to speak at all. His interlocutor laughed nervously, then asked him to talk about his dead son. (Not the best public speaking moment.)

Each section begins with the terrible trauma of some person. (Who are these people? Does Jodorowsky meet them in cafes?) With their distant eyes shining, they describe to the camera the sins which have been visited upon them. They have not been loved enough. Their parents, coldhearted. Their friends the same. The world a vale of loneliness.

Then Jodorowsky would have them re-enact their birth, or cover themselves in menstrual blood, or beat a pumpkin into bits and send the pieces to their estranged family members.

I started to get a sour feeling in my stomach. It was—to me, anyway—boring. Not that I take any joy in someone else’s emotional estrangement. Or doubt the wounds of childhood. I swear, I don’t. If anything, my heart has always been a little too close to the surface.

But it was boring. Maybe I just don’t like watching French people cry. (That really could be it. I’m not ruling it out.) I began to feel nauseated in the cramped theater. This is what we all seem like to therapists, I thought. Endless, undifferentiated pain that had no real story except once I was part of the world, but when I was born, I was cut away from it.

And I began to think—what if it would be a psychomagical act of my own to walk out?

No, Sarah! Jodorowsky is a genius! You must respect him. You must respect the suffering of these people.

But isn’t one of my constant problems the assumption of responisbility for others’ emotions?

I fought with myself like this for the rest of the film. I did not walk out, although I wish I had. When the credits began, I stood up and hurried out to the hall, full of shame.

The gift in this is that it has let me take my pain less seriously. And, in some ways, to take the idea of healing less seriously as well.

I used to think it was beautiful and necessary to consider art a healing practice of special psychological significance. I guess I still do think of it as a healing practice, but no more so than it could be considered a healing practice to look at a pot of Swedish ivy and observe that it responds to offenses against its person by going on putting out leaves and making oxygen.

There is no great mastery in crying for yourself. The self is imaginary. Get out the atlas. Cry for beauty instead.

The king of cups is about emotional mastery. The cup is the vessel of containment for things which are most difficult to contain. In many ways, a good vessel has to be unlike the substance it holds. I don’t know what that means for me—clearly I am often less of a vessel, more of an ocean.

the assignment

Become bored of your pain.

writing prompt

Cry during a detergent commercial.

a chune

“Need Some Love in My Life” by Solomon Burke

This song is a serious machine. I have to be careful when and where I listen to it because it makes me CRY. Good fucking god. I just tested it out—I thought, OK, well, I’m going to tell the newsletter people about this song that makes me cry. I’m sure the self-conscious nature of that will inure me from actually crying to this Letterman appearance with a band that’s (sorry, Paul Shaffer) about 30% less hot on it than the original recording. Right? No. Not right. Still crying. What tf is wrong with me? I love a bridge. I love a song that draws particular attention to the fact that you’ve got to get yourself from one place to another IN THE SONG. I love a song where the singer is like “Hold on a minute, I’m going to talk to you good people about something important” (which you know Solomon Burke was the absolute king of). Is the king of. You can’t hear this and tell me he isn’t still with us.

credits: small spells tarot deck by Rachel Howe

Stella Maris by Cormac McCarthy

“I Need Your Love in My Life” by Solomon Burke

dear diary, tomorrow is the five-year anniversary of my first novel’s release. If you had asked me what I thought I would be doing five years later, I certainly don’t think I would have said “still working on the second novel.” But I also never imagined that people would still be reading my book, all this time after. In the scheme of things, five years is nothing, but in publishing, it’s dog years. Every season, a new crop of hot new best young clear-eyed listworthy unputdownable change your life novels by once-in-a-generation talents are ushered onstage, where they do a single pirouette at the front of the airport bookstore, then fall away into oblivion. But five years on, I still get letters from teenage girls and women in halfway houses who found Marilou good company at a time when they really needed it, and it truly blows my mind. I don’t think I could have ever imagined that gratitude five years ago. XS

Marilou has always claimed a significant piece of my heart. She sits on my bookshelf of favourites with Toni Morrison and Annie Proulx and George Saunders. She is still a wonderful miracle to me. And 14 years after my first novel being published I’m still working on my second. Fourteen. Years. 🤓🧡