A few weeks ago, I saw the Keith Haring retrospective at the Broad with an old friend, and a quote of the artist’s in the wall text caught my eye:

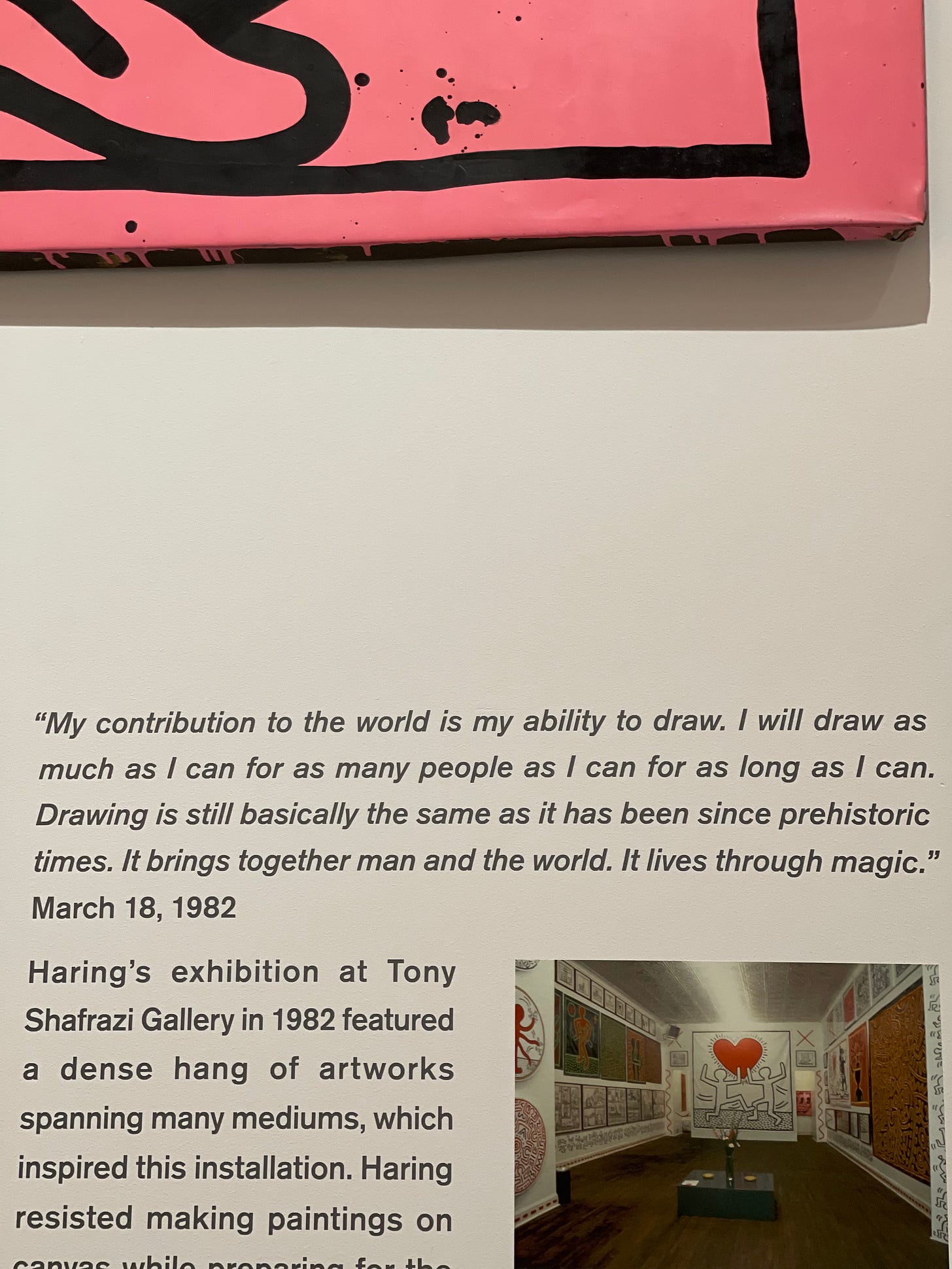

“My contribution to the world is my ability to draw. I will draw as much as I can for as many people as I can for as long as I can. Drawing is still basically the same as it has been since prehistoric times. It brings together man and the world. It lives through magic.” —Keith Haring

I haven’t stopped thinking about this quote. How direct and confident it is, and how generous as a result.

Keith Haring is one of those artists whose work I admire even though it doesn’t resonate thunderously with me. I like it, I get it, and it doesn’t go a lot deeper than that. But you have to admit, there aren’t a lot of contemporary-ish artists whose aesthetic has become a reference point of its own. You know it the moment you see it. I think you could probably buy a Keith Haring T-shirt at Target, now or ten years ago or ten years from now. He distilled a constellation of influences and concerns into an unmistakable style, and he made it his mission to produce it as much as he humanly could. Which, given the AIDS pandemic, was not as long as it should have been.

Sometimes I think: Maybe the greatest gift you can have as an artist is the certainty that your art is your contribution to the world.

When you believe that your ability to make art is your contribution to the world, you can work free of doubt and anxiety. You have nothing to prove. You don’t have to legislate a place for your work in a world that doubtlessly needs many, many other things.

And when you can work free of doubt and anxiety, you can make art that is free of doubt and anxiety.

When I was 21, I heard Mary Ruefle give a talk at the Bucknell Seminar for Younger Poets. I forget the topic of the talk, but I remember very clearly the sentiment: “Poetry doesn’t save lives. You can say that it saved yours, and that can be true, but you don’t get to say that it saves the lives of others.”

I reacted to this news like a dog being smacked with a rolled-up newspaper. It brought me up short. It stung, and I immediately adopted it as my tough-minded motto. Isn’t it interesting how quickly we can adopt a painful statement? As if by adopting it we can take shelter behind it. I imagine this might be the way we react to all shame. Shame originates from misunderstanding the world in a way that is so surprising and unsettling that you have no choice but to conclude that the error is deep within you personally. And when an error is that deep, you must immediately disavow.

I felt ashamed because actually, I did believe that poetry saved lives. Yes, in an abstract way, yes, in a way that would probably be embarrassing to try to prove in any tangible sense. I thought Mary Ruefle believed it, too. She certainly wrote like someone who believed that poetry saved lives.

Of course, that moment in the lecture was not the first time I had been given the idea that poetry is silly or inessential. But it tipped some internal balance, and I still stand on the other side of that idea, slapping myself with it whenever I sense myself getting too sentimental.

I wonder what that talk was actually about, and I wonder what was actually said. I think there is probably some subtlety that I’m missing, or which I missed at 21. The vague weightiness of the phrase “saves lives” is probably at fault here. It would be cruel if I insisted that the thing that saves my life also saves yours. But to say that something “doesn’t save lives” bears a distinct tonal meaning, one which is harsher than an ordinary reversal of logic.

Or maybe it’s because I had already been marinating in that idea, that poetry wasn’t enough, or didn’t matter as much as some other things do, that I heard that passing phrase with such sharpness.

It’s incredible that a person would grow up good at drawing and also good at believing that drawing was their contribution to the world.

Not all of an artist’s talents are aesthetic. I think many of them are talents of belief and disposition—the beliefs and dispositions that make it possible to work with joy no matter what the outside conditions are, without attention for the way the world receives everything you make.

When my first novel came out in 2019, it became indelibly clear that I lacked some talents of belief and disposition. Every word someone wrote about my book hit me like a great wind that had the power to toss me to the far corners of the earth. I didn’t believe that writing was my contribution to the world. It had to be more, somehow. It had to be good and important and popular and significant. It had to be everything! The only book ever written. Then it would be good enough to count as my contribution. Otherwise, not enough.

Writing a second novel has required me to cultivate the talents of belief and disposition that I wished I had had the first time around. You can write one novel if you think that publishing it is going to fix all your problems forever. To write a second, you have to figure out what you actually believe about books, and it has to be true or it won’t be sustainable.

I always knew that expecting the publishing experience to solve all my problems was completely terrible, a total setup. And I somehow couldn't stop myself. You know how sometimes you feel a way, and even though you could write an entire dissertation about the reasons not to feel that way and the broken logic produced by it, you just feel that way anyway, and it’s stupid, and you kind of don’t want to talk to anyone about it because they’re just going to say to you what you already know? It was like that!

Humility is tricky. It becomes vanity in a heartbeat. You can use the fantasy of it to beat yourself to death. You can hide behind the idea of it, but the actual practice is rare. How many resentful acts are carried out in its name?

During my most spiritually obedient years, when I was good AA girl, I did a lot of service in the name of humility. “Service” meant lots of things, but it especially seemed to mean “things you don’t want to do.” Tasks not tainted by self-regard or egotistical motives. My former sponsor gave me this distillation of steps six and seven: “Don’t do what you want to do, and do what you don’t want to.” Presuming that anything you wanted to do was selfish and sinful by default, given your fallen nature. (

The Keith Haring quote is striking because it’s a demonstration of actual humility. If you believe that drawing has magic in it, and you are skilled at it, you do it. For as long as you can, for as many people as you can. Even if it’s what you love doing, and even if there are other ways of serving the world. Even if it doesn’t save lives. Although who knows? Lives can be saved from tedium and alienation. Lives can be saved from meaninglessness.

For a trial period, I’m going to make this my motto and goal, too. And see where it takes me. Because I think writing lives through magic.

Thank you for reading! After 1 week, all posts go into the archive for paid subscribers. If you enjoyed reading this, subscribe to catch it when it’s hot!

If you’re a longtime reader of this newsletter, you’ve seen god knows how many pictures of Falkor. I’m sad to tell you that he passed away a few weeks ago, and we miss him tremendously. I hope you’ll remember him today by giving your kitties and pups an extra squeeze. Talk about living through magic.