CW: I write about my experience with body stuff and weight loss here. If that is tricky material for you, come back another time.

In volume 1 of this series, I realized that, even though I did Richard Simmons’ Sweatin’ to the Oldies religiously as a child, I had no recall whatsoever of how I began. And similarly, I have no idea how the Tae Bo tapes made it into the house. I remember seeing the infomercials on TV, and then their mysterious appearance. I remember the way doing roundhouse kicks on the second floor of the rickety farmhouse where I grew up seemed to shake every floorboard. It kicked my ass. I always got that hardcore beet-faced asthma prickle when I did it.

Had I asked for these tapes? Had my parents ordered them for themselves and then simply never used them? I was in high school by then, so I guess it wasn’t totally impossible that I had asked my parents to order the tapes, although that doesn’t honestly sound like something I would have done. But anyway, just like Sweatin’ to the Oldies, once the Tae Bo tapes appeared mysteriously in the house they became my sovereign realm.

When I look at pictures of myself from high school, I can tell you for sure that I wasn’t a fat kid any longer. I was consistently a size 12, more or less, and I was active much of the year in marching band. But it still felt like I was on the other side of a decisive gap and couldn’t cross to the other side until I was a size 6. I felt like my body was a tragedy, maybe the greatest tragedy of my life, because its size represented my loneliness. I was a secret eater, so my fatness also functioned as an index of the amount of time I had spent alone, the degree to which nobody was paying attention.

Which wasn’t how I would have described it at the time, of course. At the time it just felt like a sense of pervasive failure, and the reason that compliance with a set of exercise tapes was still necessary. I wrote in the last installment of this series how being a fat kid is kind of like being a sleeper agent: You have directives which your classmates and friends are totally innocent of. Half of your mind is always somewhere else. You are on a mission, although it isn’t clear how you got there. With Tae-Bo, my training escalated to combat. But who or what was I training to fight? My own body, or the people who had teased and tormented it? I still can’t tell you, but I can do a pretty sweet roundhouse kick on command.

That was just the first chapter of my time with Billy, though. In 2006 I bought the Billy Blanks Ultimate Boot Camp DVD at a Best Buy on my lunch break when I was teaching poetry outreach classes in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. This is the first time that I actually purchased an exercise program myself. A few months before that, I had taken the train to Philadelphia to meet up with a guy I knew there, a guy who I had flirted with online ever since we had met at the PA Governor’s School of the Arts, a program that brought together exceptional art kids from across the state for a six-week sleepaway summer camp. (The first time I was surrounded entirely by other art freaks. Heaven. It was heaven.)

I was in the poetry program, and this guy, let’s call him Stewart, was in the fiction program. He was a massive dork, but a hot dork. I don’t know what finally catalyzed this trip to see him. It was a romantic gesture, and such a brave one, and it was also one of the worst weekends of my life because from the first moment he saw me, he was visibly disgusted with the weight I had gained since high school. The only self-preserving choice would have been to turn around and get on the next train back to Pittsburgh immediately, but I didn’t know how to make that choice then. I truly didn’t. So I hung around all weekend while Stewart tried to lose me in public places. Literally—we would go to the park or the coffee shop and when my back was turned he would disappear. It was like a Mary Gaitskill story, except actually happening to me, and at the time, the message I retained from this wasn’t “This person is cruel in a way that defies understanding.” And not even “I am cruel to myself in a way that defies understanding.” It was: “Lose weight and this shit won’t happen again.”

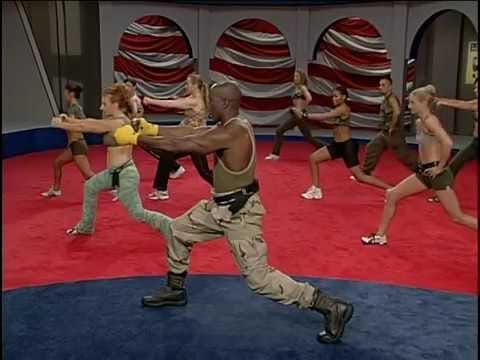

Ultimate Boot Camp doesn’t take its title lightly: The bloc of participants behind Billy are all wearing military-inspired gear, some little booty shorts with a camo crop top or whatever. Billy is wearing camo cargo pants, and of course one of those trademark tank tops that show off his pecs. Like all boot camp workouts, the emphasis is on basic calisthenics done past the point of exhaustion, but occasionally these have slight combat overtones, like doing a push-up and rolling your body to the side of the room to do another.

This was, without a doubt, the most extreme form of training I had ever done. I was a bookish kid. The only time I participated in a team sport was basketball, in sixth grade, where I was constantly terrified, exhausted, out of breath, and ashamed. I wasn’t just bad at it—I was hopeless. After the intramural season, they “selected” from the teams to make up the school’s actual competitive team, and they selected every single person except for me. I got a participation trophy, of course. (Oh, I know people love to bitch about millennials and participation trophies, but what they don’t know is that sometimes getting a participation trophy feels even worse than not getting one.)

I considered myself non-competent in all forms of exercise. I think I might have used the gym at CMU two or three times, but that’s it. It felt like it belonged to other people, the way it felt like god belonged to the fundamentalists I had gone to high school with. The idea of trying to get stronger and doing so in public was impossible to me; I was still so embarrassed about being the worst ever basketball player at Cameron Elementary.

But Tae Bo Ultimate Bootcamp was the beginning of a different self-concept for me. I mean, listen: It was hard. Like, hard hard. It’s a solid hour of squats, lunges, burpees, roundhouse kicks, and push-ups, and doing it every day turned me into the kind of person who could do those things. Because I was fucking sick of it. Doing something extreme seemed warranted. If it hadn’t been for Stewart’s cruelty, and my own self-inflicted cruelty, I probably would have simply given up.

There’s a part at the very end of the workout where you have to hold a squat for who knows how long while Billy tells you direct-to-camera that anybody can do the first 15-20 minutes of a workout physically, but past that, your mind and your will have to do the rest. The exercisers behind him are straining and trembling, their eyes rolling like the eyes of war horses. And he has them repeat, call and response style: “Where I am today is where my mind put me. Where I’ll be tomorrow is where my mind put me. So look at yourself. Your mind put you where you are today. And you can change it any time you want.” All along, I had complained to my parents: The world is unfair. The beauty standard is inhumane. People are shallow. Am I just supposed to pick up and go in my own direction and love myself anyway, even though it’s so hard?” To the best of my knowledge, my parents answered this question with some neutral, noncommittal statement. But in my experience, the answer is: Yes, that’s exactly what you have to do.

The Richard Simmons organization is tightfisted with YouTube clips. You can’t find that much material out there. But Tae Bo doesn’t seem to give a fuck, because you can find pretty much everything in full. So I did Ultimate Boot Camp again, and like … it was kind of easy. I mean, it’s still an hour of calisthenics, and I still hate burpees. The music is really fucking weird. It was clearly written just for the DVD because the lyrics are like: “C’mon Shelly c’mon Shelly! Work that belly work that belly!” (True Billyheads will know that Shelly is his daughter, and she steps in to cue whenever Billy roams around to fine-tune pushup form. And her favorite snack is pineapple. ANYWAY.) I remember sweating all the way through my shirt when I used to do Ultimate Boot Camp. And now it’s a mildly challenging but totally doable task. I do not see my body as a tragedy. I still occasionally feel bad when I can’t fit into anything at the Levi’s store (it’s because of the hips—I’m a size 8 with infinity hips, and Levi’s is not down with me. And if you want to take my black high-waisted skinny jeans, you’re going to have to run me over with a car). I am pretty healthy, mainly because I have a low tolerance for feeling bad. People who have met me within the last five years would probably not imagine that for a large part of my life, the mere existence of my body felt like evidence of a deserved abandonment.

You could tell this story as a triumph of my mind over my body. You could also tell it as a triumph of my internalized shame over my body. You could feel sorry for me, or think this represents an abandonment of self. You could call it a garden-variety success story and put it in Women’s Health (which I used to read fervently, even though all it ever told me was fiber, protein, fiber, protein, interval training, but like don’t forget to have fun!!!). But this is what I’m always trying to tell people about stories: life itself is a firehose of experience, sensation, incidence. It is an undifferentiated swell of happening. A story—even just the self-narrated version of the past—is a composed selection of material from that swell of aliveness. There is an infinite gradation of available stories depending on where you drop the frame and which moments you privilege.

When I’ve written even obliquely about my history of body stuff, I’ve been surprised how people pop out of the woodwork to scold me for acknowledging or representing the desire to lose weight. Even just referencing it, no matter the context. Which is part of why I haven’t written much about these things over the years. People take it very personally, how you arrange your own past, how you tell stories about yourself. You could say that the war I was preparing to fight in Tae Bo Bootcamp was a war against my body, and an essentially self-hating gesture. But for me, being strong was the beginning of being able to love myself. For me, it was a war against my mind, against the idea of myself as incapable and inert and doomed. and for that reason I will always love Billy Blanks. For real.

I initially started this series because I was wondering: What happens when you stare at a face for hours and hours in a strange state of physical exertion and hypnotic focus? What do those faces do to you, where do they go inside you? How do they change you? But the face is neutral. Richard Simmons’ body diversity and good vibes don’t really translate if you’re dancing to escape what feels like a failure inherent to your soul.

I was going to put out a third volume, but it’s kind of exhausting. I want to write other things and feel like I can’t until I wrap this up. I was going to cover Tracy Anderson next, but all I really have to say about her is that the early 2000s club music in her mat workout DVD is sublime, and there’s an oblique reference to her in a Tommy Pico poem—like, a deep cut reference, which you would only get if you were also a massive Tracyhead—which makes me happier than it maybe should. But that’s all I really have to say.

I looked Stewart up on Twitter, and it seems like he’s become a pretty good guy. He’s a policy wonk for a medical foundation. He retweets Black Lives Matter and seemingly works from the framework of understanding economic inequity as a public health issue. I wonder if he remembers being cruel. But I guess it doesn’t matter, because I do.

Join me next time for something less fucking long and harrowing! Perhaps.