[Ed. note: What follows is the text of the keynote address I gave last week at the Writers’ Conference of Northern Appalachia. Thanks to everyone who was there, and for inviting me to speak—for reasons that are obvious in my talk, being invited to speak to and about the region was really meaningful to me. I realized during the conference that a lot of that placeless feeling which I took so personally was actually a really common experience.]

When I arrived at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, I did not think of myself as an envoi of Northern Appalachia, although to the observant, there were signs. I detested pity—self and otherwise. I favored absurdism, which to me has always seemed, if not real, at least honest. Nature frequently figured in my stories, not so much as a backdrop but as another character, or even a friend. And I had no idea that “needs done” was ungrammatical. Surely, if something really needs done, you don't have enough time to throw “to be” in there.

But I was soon to discover that my sense of reality was, at least as far as my peers were concerned, miscalibrated. Fiction workshops can be good—I guess—but they can also devolve into courts in which the nature of reality is debated by people who are not really qualified for the task. Often enough, this debate concerns whether a character's actions are realistic, whether certain events have been earned by the plot. But it also by necessity concerns the worlds in which those characters are rendered. A person can make no sense without a place to make it in.

And so, in fiction workshops, I found myself struggling to make any sense to my peers. Once, in reference to a story set in Greene County, where I am from, a friend of mine said—I just can't visualize the town where this takes place. And I would say—there is no town. And he would say, what about the other houses? And I would say—there are no other houses. The nearest place is an empty hunting cabin full of snakes. And he would say—so, where is the town?

This confused classmate of mine was a Pultizer Prize-winning journalist. He had extensively covered the Tibetan steppe, and wrote beautiful stories of frostbite and yak milk yogurt. But my tale from the land of Sheetz had completely baffled him.

In the revision process for my first novel, Marilou Is Everywhere, my editor asked me why there were so many scenes that take place at gas stations, and why all the gas stations had Polish names. Why not at a library, why not at a grocery store? Because there aren't any of those things, unless you drive half an hour. An educated, upper-middle-class professional from New Jersey, she didn't believe me. She had never heard of such a thing.

Eventually, it became a hobby of my mother's to tell me any local news that would confound my fiction workshop. That two brothers had shot each other over a stolen TV, for example, or a goat had been stabbed in a revenge spree. Or the time that a medical research truck full of rhesus monkeys got lost on One-Armed Lady's Road which—yes--is so named because a one-armed lady once lived there.

That last one got covered in the newspaper. The article is titled: One-armed lady existed in local area.

And there was another problem: Often, my classmates would call my rural characters “unrealistic” because they were “so intelligent.” How could this person possibly have a mind that makes such poetic connections? they would say. How can a person be this generous? It's not real. To them, a rural character who was also intelligent and sensitive was unrealistic, full stop.

In my mind, I would howl: Who do you think wrote the story?

But of course, that's the other part of the problem. While my rural nature itself didn't make sense to my peers, I also didn't seem country enough to write it.

Maybe one of the reasons I didn't consider myself an envoi to Northern Appalachia was because I wasn't completely sure that I counted. Of course, if you asked the census bureau, I did absolutely—I was born in Wind Ridge, Pennsylvania, delivered by Doc Sonneborn, a country doctor of the old vintage who was frequently completely wrong about due dates. He had a habit of telling women who were already mid-delivery that it was just gas pains troubling them, and sending them home, where they would have their babies in the bathroom.

Believe it or not, I went to school with lots of kids who were born at home—into the toilet—thanks to Doc Sonneborn.

I can show you the baby pictures where my diapered butt is sitting on a table made out of a cable spool. We used to wash our hair in the pond. My sandbox was a tractor tire with sand poured in it. And once, when my mother was getting dressed to go to a party, I apparently said to her: “Momma, why you puttin' on your city? You a country girl.”

I've tried to put that line in dozens of stories, but it's obviously meant to be a song.

I grew up on a road called Herrod's Run—yes, Herrod, king from the bible—but unless you call it Herd Run, nobody will know what you are talking about. There is a sign at the end of the road that says PREPARE TO MEET THY GOD.

To this day, you can't get cell phone service on the run where I grew up. It is too remote, too deep in between the hills.

When I lived in Austin, my friends and I took a drive out to Big Bend National Park in the spring, and somewhere between Ozona and Marfa, our cell phone coverage disappeared.

My friends were shocked at this. As we traveled through the remote, gorgeous landscape, one of them said—can you imagine what it would be like to grow up in a place like this? So far from society that a cell phone wouldn't even work? What would that do to your brain? What kind of person would you be? They envisioned bleak scenes of Cormac McCarthyesque depravity—certain madness caused by alienation. A life of banishment to the outer darkness. I, of course, said nothing.

But if you consulted the people I grew up with, it wasn't quite as straightforward. For one thing, I didn't have any relations—my extended family lived in Ohio and the upper midwest. I didn't have the accent. And my parents had strange habits. My father didn't hunt, my mother sent me to school with homemade whole wheat bread. They were educated and opinionated, and when a neighbor came to welcome my father to the neighborhood, asking if he had accepted Jesus Christ as his personal savior, my father said, “I sure hope so!”

I grew up on 250 acres of old forest and disused farm. The barns that were standing when my father bought the land have slowly fallen, one by one. I admit, I still don't entirely understand what would make my father call up a man in the Post-Gazette classifieds and buy this land sight unseen. Especially because my parents would prove to be so baffling to our soon-to-be neighbors. My dad had long hair, a beard, and rainbow suspenders. My mother, Moosewood Vegetarian Cookbooks and Cat Stevens records.

In the land of doublewide beauty parlors and realtree camo everything, my parents were New Yorker reading, NPR listening, card-carrying progressives who liked to brag that as a baby, I teethed on a copy of Saul Alinsky's Rules for Radicals. They both grew up working-class, my father on a hog farm in Storm Lake, Iowa, and my mother raised along with four siblings on my grandmother's secretary salary. In terms of class, they should have fit in, but culturally they couldn't have been more different, and that difference rubbed off on me.

I wasn't aware of this difference until others made it plain to me. I remember crouching at the top of the stairs in my best friend's house, our mothers talking over coffee downstairs at the table. “Sarah uses too many big words,” my friend's mother said to mine. “You have to get her to stop. It makes the rest of the kids feel bad.”

This came as a shock. I had no idea that I was using big words. And it alarmed me to find that I was capable of making others feel bad without having any idea that I was doing it.

At that moment, my double came into existence. My twin. I stood outside of her, trying to figure out what was wrong with her. That's the kind of disposition that will absolutely make you a writer—and not necessarily a happy one.

I bring all of this up, mainly, because it seems to mirror the position we find ourselves in here, in Northern Appalachia—we are too Northern to be Southern, too industrial to be rural. In college, the kids I knew from the Midwest considered Pittsburgh to be an east coast city. The kids I knew from the East Coast considered it to be an annex of Ohio. I have always been too country for the Ivy Leauge and too verbose—I guess—for ruralia.

And for a long time, I found this to be a profoundly lonely position—one that I tried to write my way out of, as if I might somehow eventually prove that my life was really true. If I could—what? impress a writing workshop? Convince some 24-year-old whose life experiences consisted solely of going to Columbia and interning at Vogue that my life was worth documenting? I had a chip on my shoulder, and I didn't think very highly of the people whose approval I sought, but I courted it nonetheless. I tried harder to translate myself, to cross-examine my double. There was a riddle to this, one that drove me to work and also drove me to exhaustion.

There are some people who want to read only the kind of stories that they've read before. There are some people who want to experience a very limited range of beauty. I have never been one of those people. In fact, I have not always been able to hide my disgust of them.

But nevertheless, it is true—the apetite for the expected is a considerable market force. A million superhero movies. Everything a remake of something that was once new. Publishing has been especially risk-averse lately. My agent has told me that even the most straightforward “easy sell” books have been taking a long time to land anywhere. Everybody wants something new, but they don't want to be uncomfortable, or they lack the bandwidth to understand something that doesn't reveal its moves immediately.

A market force may as well be a political force as well—none of us here need reminding that our current vice president got to where he is now in great part because he was willing to tell a certain tired story about who we are here, and what we're capable of.

This story—the sad one, the poverty porn version—is a resource which is extracted from our landscape just as our coal and gas. It is putrified, compacted, highly flammable.

All of which, to my experience, anyway, has been true—but I didn't know what to do with it.

But I recently discovered something that has helped me very much on this score. A few months ago, David Lynch, one of my heroes, passed away. In Twin Peaks, he had told a story that was cosmic and particular and haunting, while somehow also being corny and good to its heart. That show was home to me in part because its contradictions felt true and honest—even the most ridiculous, campy aspects of it felt fundamentally honest to me. I had watched it as a child—another interesting parenting decision, I'm sure you'll agree.

I had always wondered, how did this show end up on ABC? How did David Lynch manage to feed this strange stew to a massive, mainstream television audience? He had somehow succeeded in holding so many contradictions while also garnering a massive audience for something challening, experimental, and occasionally opaque. I wondered if this was because he studied genre tropes, if there was some secret barebones Freitag's triangle structure, or if it was just that he succeeded on the strength of some personal force which I lacked—if, in other words, he was just really cool.

But the honest truth is that his work succeeded because it was a gift.

I realized as I read countless appreciations and obits that for many, many people, people like me, David Lynch's work had made a space. Opened a door. He did not do this by being understood, but by trusting the impulses that moved him, and trusting people to make something good out of what they saw, if they saw it.

Of course, there were many people who didn't care for David Lynch's work at all—I'm sure there were many, many more people who found its mysterious logic inscrutable and annoying.

But at his passing, none of these people appeared in print to say: “Eh, I never liked him. I thought his stuff was inscrutable and annoying.” Because if they had, that would have been a bit ghoulish. And because in the final tally, the connections matter more than the misses.

I started to realize that I'm not really giving much in my work if I demand to be seen and understood as I give it.

This unlocked something for me, and I share it because I hope it might unlock something for you too, especially if you also write from this strange kind of doubled otherness, this prism that puts you somewhere outside yourself.

It can be painful and lonely to feel as if your world is unrecognizable. But if your world is unrecognizable, that also means that you bring good news, strange tidings, something new. It means you are capable of opening doors that weren't there before.

It takes effort to give this gift. The grace of it is in not knowing how it will be accepted. I think that this is true for all writers.

In the book The Gift, Lewis Hyde connects the idea of a gift economy to the act of artmaking. “Works of art exist simultaneously in two 'economies,' a market economy and a gift economy. Only one of these is essential, however: a work of art can survive without the market, but where there is no gift, there is no art.”

“A gift must always be used up, consumed, eaten. The gift is the property that perishes.” For this purpose, the gift is consumed as soon as it leaves your hand—no matter what eventually becomes of it. No matter whether it makes sense, in other words, or garners praise. No matter whether a 24-year-old Ivy League student who knows only Columbia and a Vogue internship finds it realistic.

Of course, you may consider the gift to be the artist's skill, or their reception of sudden inspiration. But I think you could also very much consider their raw material—their access to lived experience and memory, their willingness to report, tell the truth, show the pictures.

David Lynch was an exceptionally talented giver because he could fish a strange, incredible image out of the deep waters of his consciousness and because he could give it, open-handed, to anyone who would take it without demanding their praise or understanding.

In summer 2024, my partner and I went to Japan, landing in Kansai International Airport on the coast outside Osaka. I had no idea what to expect beyond the sentimental, hushed scenes of the Japan Airlines Welcome video that played when we landed: a single brushstroke of elegant sumi ink, a single grain of matcha falling through a sieve, etc.

So I was happily surprised when our taxi drove past a row of hunched mills and industrial buildings crowned with icy white lights, reflected in the water of the inlets. It looked almost exactly like a drive through Mon Valley mill towns. “I never knew Osaka was so beautiful,” I said. And I meant it.

Because that is my beauty. It is the beauty that was given to me, and it is the only beauty I have to give.

My gift was mayapples. Fish fries. Sheetz shmiscuits. A front porch made out of a cracked cement slab. Black snakes that can crawl up windows. Words that are too big, which make the other kids feel bad. Being outside of things in more than one way. The gray, gray, gray headache light. The football game on in the background, the bare hills, the blue sky. The mills, the coal mine, even the gas well that rushes all through the night, like an imported ocean.

It wouldn't be a gift if I hid the parts that are ugly, and it certainly wouldn't be a gift if I used it in the service of political expediency.

Take me to a nothing town with a bar that smells like fryer grease and I will go: oh yeah. There it is. Sometimes I see a twinkle on the horizon, some beautiful lights ahead in the distance and when I get closer: it is a dive bar. Or it is a coal chute. That beautiful petal green color of the Consol Mine. We always called the lightbulbs on its spine Christmas lights.

I used to think that I had to fight for my beauty. I thought this because my beauty emerges into a world that does not already know how to see it. The market economy often sees my beauty and says what? and no thanks.

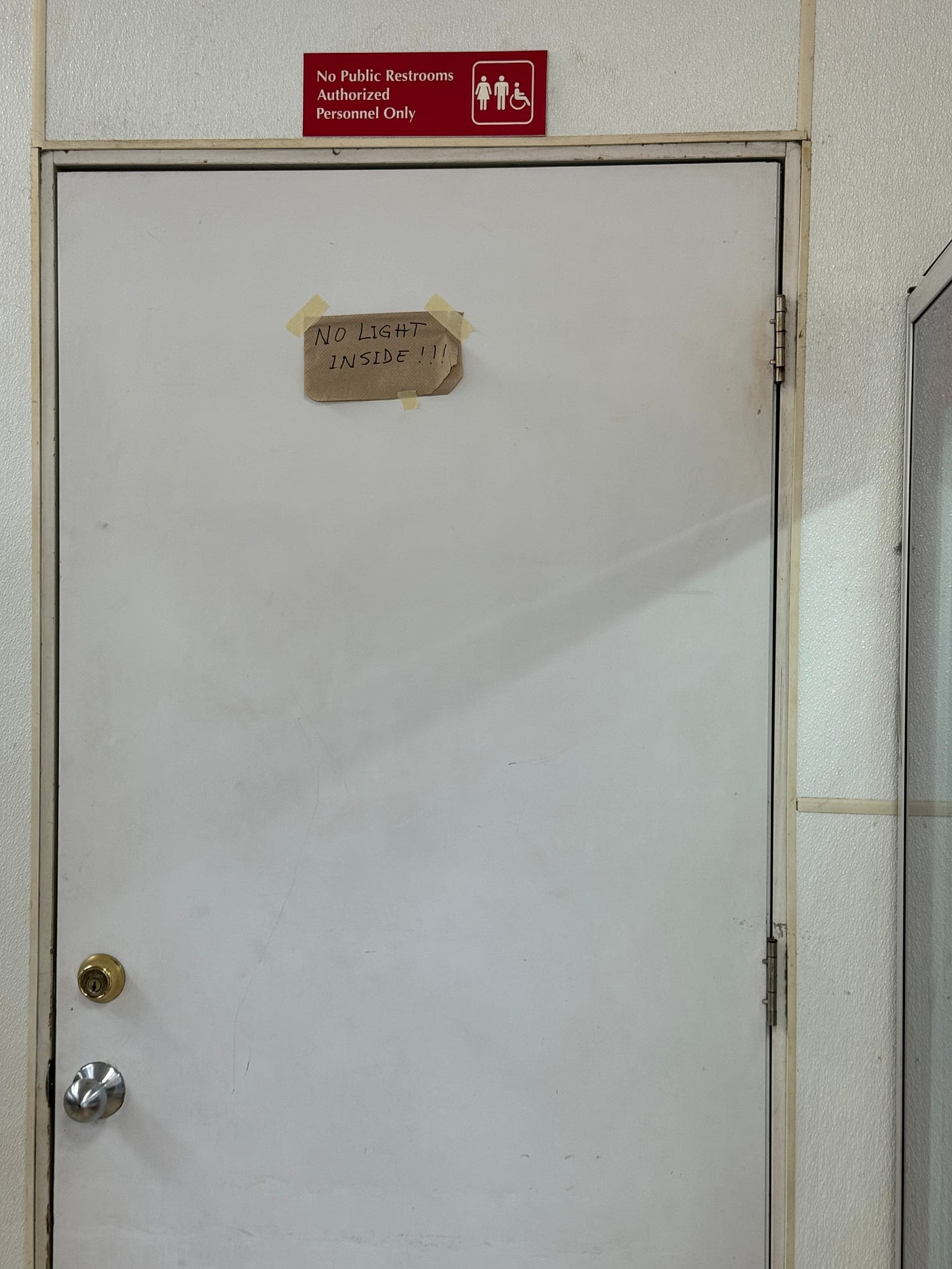

But for that reason it is strange, and for that reason it is incredibly precious. We live on the ragged edge of an important beauty, a continent of beauty, an ugly beauty with stupid highlights in its hair and a cherished collection of blue blown glass basset hounds perched above its kitchen sink. A beauty of snakes. A beauty of barn wood aged gray. A beauty of misspelled signs at the laundromat.

Happily for all of us here—we know that it is a gift, and today we get to share it with each other. And I hope that this will help us be wildly generous in sharing that gift everywhere else.

Thank you for reading! If you’re a new subscriber, welcome! Usually this missive is a bit more … oblique? Informal? Oh well, you’ll see! Till next week. I’m going to go make some tahini-miso-lemon sauce. XS

I was at this conference and had the privilege of hearing this live, and the rest of the day was such a whirlwind that I didn’t get the chance to catch you to say thank you for this. I felt so connected in that room during your keynote. Stripped raw and seen and understood. I’ve told a couple of people close to me about the power of your words, and I’m very happy to see this here so I can share it with them!

This greatly moved me. I keep learning new things about you. Your words about Lynch here really bring his genius into focus. This is quite brilliant. I feel like you may be the Annie Dillard of Northern Appalachia.